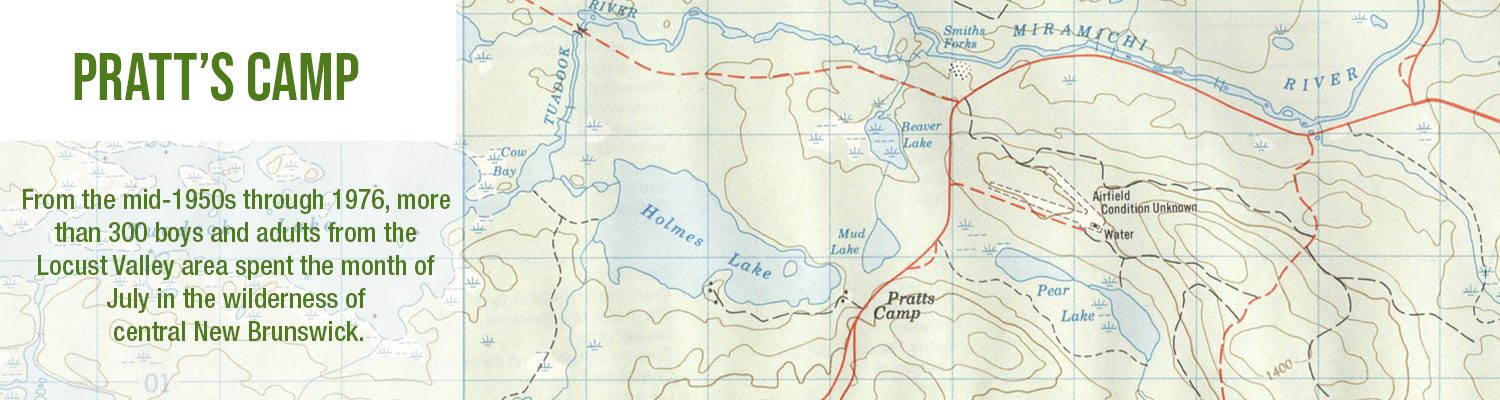

The Winter Camp

This cluster of log cabins and frame buildings was the base of operations for the camping program. Located on the east end of Holmes Lake, it was called the Winter Camp because the cabins had insulation, unlike the buildings across the lake in the Summer Camp. In the 1950s, there were five buildings: two dormitory cabins, one camp director’s cabin, a cabin called the Day Room (the camp’s “living room”), and a multi-purpose building that was kitchen, cook’s quarters, and a small dining area.

In the late 1950s, a new dining room was added which was capable of seating all the campers and staff. In addition, three platforms for large wall tents were added to increase bed capacity. In 1963, a much larger log cabin, the New Day Room, was constructed. A third dormitory cabin was added in the later 1960s.

A typical day in the Winter Camp began with breakfast, followed by domestic chores like bed making. The remaining morning could be devoted to swimming, canoeing, fishing, or short hikes. Lunch was followed by water skiing, sailing, hiking or whatever you wanted to do that you hadn’t already done.

A volleyball court provided nightly competition, a round-robin event with winning team getting a treat. The prime prize was a Cherry Blossom, an oversized gooey chocolate-and-syrup concoction. There were horse shoe pits to occupy downtime. And campers could always take canoes out for a little end-of-the-day fishing.

Darkness came late in the New Brunswick summer, but there was electricity in the Day Room for an hour or so when the generator was cranked up. Popular card games played included pinochle and cribbage — but the mainstay was hearts.

There was also a pit for occasional campfires — but as a rule, evenings were so buggy that campers tended to spend that time indoors (the three primary insect antagonists were mosquitoes, blackflies, and tiny biting flies called mingies or no-see-ums).

Campers also rotated through shared work duties ranging from setting out hot water for pre-meal wash-ups, to tidying up the grounds, to helping to clear trails. Your laundry was a personal responsibility that required using an antique hand-cranked washing machine. So there never was a shortage of things to do when you were at the Winter Camp. In addition to all the regular camp activities, there was ample time for traditional horse play, and boys-will-be-boys pranks.

On the Trail

There was lots to do on Holmes Lake, but the real deal was going on the trail to the remote camps. In the early years, there were seven: cabins at the Upper Forks, Pine Tree Pool, Renous Lake, and North Pole Brook; and lean-to’s at Smiths Forks, MacDonald’s Pond, and Pocket Lake. There also was a cabin on an island in Tuadook Lake, owned by a Dr. Lockhart, that we could use.

In later years, the North Pole Brook camp became unavailable, the Smith Forks lean-to was replaced with a cabin, and a new lean-to was built between the Upper Forks and MacDonald’s Pond at Guy’s Pool (although this feature had other names).

Each camp had its own character and appeal. The all-time favorite was the cabin at the Upper Forks. To get there, you hiked 1.5 miles from the Winter Camp to Smith Forks (if you were lucky, you got a ride in Hubert’s truck for this part of the trip). Then you crossed Cow Bay Stream (by wading or by a footbridge) and hiked another 1.8 miles through the forest with red squirrels and deer flies for company. You came to a boathouse on a long deadwater of the Little SW Miramichi.

You transferred your pack to a canoe and headed upstream for another mile of paddling before reaching the Upper Forks cabin. Upon arrival, the first order of business was removing the window shutters and opening the skylight in the wood-shingled roof. Then you staked out your claim on the platform bed that occupied a third of the cabin’s interior.

If eating was the next order of business, someone had to stoke a fire in the stove and get a kettle of water from the spring. After lunch and cleanup, fishing rods were unpacked and campers headed for spots with names including McCormick’s Spring, Fetzer’s Hole, and, most famous of them all, The Salmon Pool. There were many other spots to explore by canoe. Part of the fun was venturing beyond “known” territory and imagining you were the first to be there.

The routes to the other remote camps varied, but the ultimate test of woodsmanship was going to Pine Tree Pool, the most distant of these destinations. That trip was a day-long trek of hiking, canoeing, and portaging. Your effort was rewarded with a view of a majestic pine tree that gave the camp its name.

On the Water

Hardly a day went by when campers didn’t get wet. Although chilly compared to Long Island Sound in the summer, the waters of Holmes Lake were always an inviting resource. Besides recreational swimming and fishing, campers could take courses in lifesaving, learn to waterski, or sail in a small fiberglass sloop.

For inexperienced campers, the first order of business was learning about canoes and water safety. If you didn’t know what a J-stroke was, you soon learned. Once you acquired the basic skills, canoes were your ticket to explore, fish, or just enjoy a tranquil paddle.

The Winter Camp had plenty of canoes. Many had distinct traits and features that earned them names like The Pig, The Sieve, Old Tippy, or The Little Gray. Some were well-used and had seen better days. A few were just about brand new. Mostly all canoes were traditional wood and canvas construction in the 15- to 17-foot range. Wooden paddles were also standard.

In the remote camps, there were several memorable canoes. The boat house on Renous Lake had a larger sponson canoe that could easily handle four passengers and their gear. An even larger sponson canoe was kept near the dam at the outlet of Tuadook Lake (a.k.a. Big Lake). There was also a large aluminum canoe used on MacDonalds Pond. But the grand daddy of them all was the Johnson War Canoe used at the Upper Forks. This monster could take as many as ten campers and their gear.

Power boats on Holmes Lake also changed over time. In the early years, the “speedboat” was an intricately hand-crafted wooden beauty powered by a Johnson 15-HP outboard. This served as the camp’s water ski boat until the arrival of a larger and more powerful craft that was better suited to the task in 1963 (for the record, the 15hp wooden boat described above was still in perfect working order, engine and all, in the mid 1990s!).

There were always several smaller outboard boats used to ferry campers across the lake or fishing. One of these was used for the daily task restocking the Winter Camp kitchen with ice from the ice house at the Summer Camp. Holmes Lake was also the camp bath tub, and Ivory was the much preferred soap because it floated!

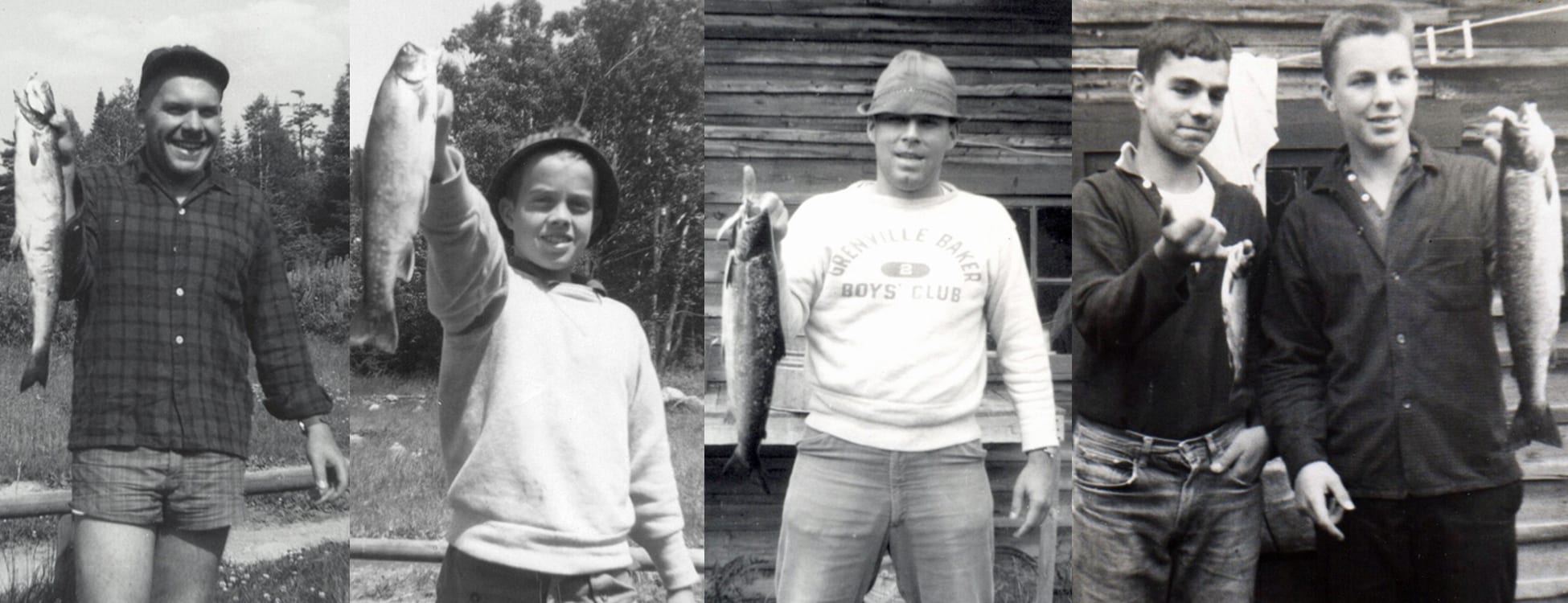

Fish Stories

For kids used to bottom fishing in saltwater, fly casting and its related skills presented a challenge. In the first few days at camp, just about any available space was occupied by a first-year camper trying to get the rhythm down, or by experienced campers refreshing their abilities. And you didn’t have to go far to put these skills to use.

The emblem of angling accomplishment was landing a fish that was large enough to merit a tracing. Both Old and New Day Rooms had their walls, and their share of trophies. Any grilse or salmon was worthy of a tracing, but a trout (in general) needed to be around 16 inches in length or longer to warrant a place.

On Holmes Lake, the two hot spots for trout were the spring hole on the south shore between the Winter and Summer Camps, and the lake’s inlet in its southwest corner. There was a short trail from the lake’s west shore to the dam at the outlet of Tuadook Lake, and Cow Bay Stream was a short cross country hike from the lake’s northwest corner. Both sites were renowned for trout, especially early in the month. That held true for the other camps, except for Renous, which had a reputation for being fishless.

Trout were considered fairly easy prey, although large trout could be elusive. The supreme goal was a grilse (the traditional name for a smaller Atlantic salmon). For that prize, you had to fish in a river. The camp on the North Pole Brook was perhaps most legendary, but very few campers got the chance to fish there. In the lower section of the Pratt’s lease, campers fished at places called Corner Pool, Moose Landing, Halfway Rocks, Eliot’s Pool, and Smith Fork (aka Lower Fork). These were places where campers waded and fished in faster -moving water.

Angling at the Upper Forks, on Holmes Lake, and similar sites was different as there were few places suitable for wading. Whether for trout or salmon, you usually fished in a canoe. One person fished while the other paddled — then roles were switched.

Salmon have a habit of jumping out of the water for no known reason. That made their presence well known while heightening both the desire to catch one and the frustration of not being able to do so. It wasn’t easy to get a grilse to take your fly — and if hooked, they were not easy to land. Not everyone was successful.

Even Camp Directors got in on the action!

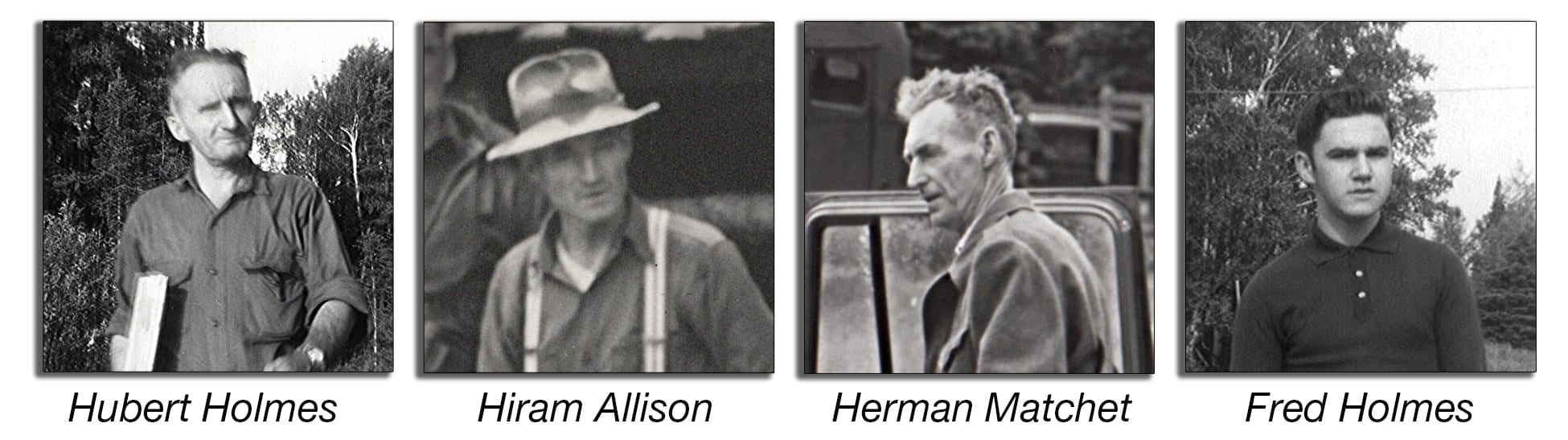

The Canadians

Campers brought a lot of Long Island culture with them, but they were in another country. For many, it was their first international travel. From the earliest days of the camp, the Pratt family relied on Canadians to maintain the facilities on Holmes Lake and the remote camps. Some of these relationships lasted for decades.

During the Club’s July occupation, there was always a resident staff. Typically, that included a licensed Canadian guide or two, a camp cook, and an assistant cook. For most campers, these men became friends and highly esteemed mentors.

Of these, Hubert Holmes was the MVP. He was superintendent of the camps. He was a skilled and experienced woodsman, and a man of infinite patience, unique grace, and memorable humor. He befriended easily and readily engaged the campers and counselors.

He spoke with a distinct Provincial accent that included a host of idioms and phrases that the campers tried respectfully to emulate. Boys were lads. The word trout was pronounced troot. His highest compliment was saying some-thing was the very, very best. And, if he answered a question in the affirmative, it was “yes” but it was spoken with a slightly inhaled breath.

He wore green pants, a green shirt and a fedora-like hat. His belt was adorned with Canadian Guide badges extending back twenty years or so. He had a dusty pick-up truck and drove those less-than-perfect gravel roads with something akin to contempt. If you were riding in the truck bed, you held on for dear life.

Hubert pretty much stayed in camp and kept the facilities running. Another guide was on hand to help with trail trips. In the 1950s, it was Hiram Allison. For the 1960 season, he was joined by Francis Foran (Hubert’s unofficially adopted son). In 1961, Hiram retired and Herman Matchet took his place.

Herman remained a fixture over the next years. He was a soft-spoken but opinionated man with a wry sense of humor and a curious laugh. He also had a reputation for telling slightly risqué jokes. In addition to his skills with an axe and canoe paddle, he was an able angler who helped many a camper learn the intricacies of fly fishing.

Over the years, a variety of cooks and assistants kept food on the table. Among them was Billy Holmes and his son, Fred. Billy was Hubert’s brother. In the later 1960s, the main cook was a man named Vin Murphy, renowned for his doughnuts. All these men were famous for the quality and quantity of food served.